The Mess

Why leaving that scratched-out, torn-up, mistake-filled page in your journal is actually a good thing.

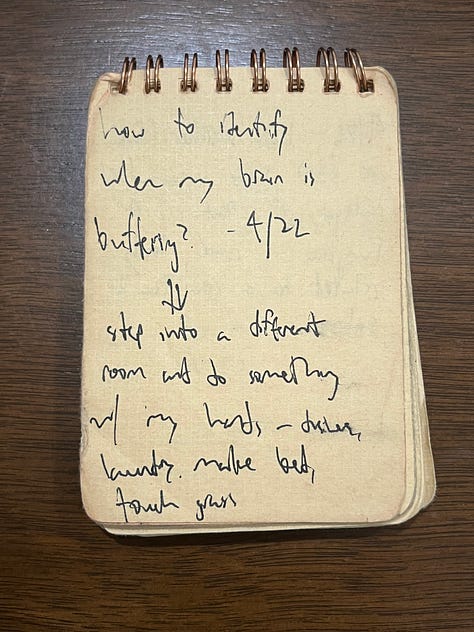

For maybe a year or so, I've been carrying this tiny notebook in my front-left pant pocket. I bought it on a whim at one of those boutique craft stores that also happens to be a coffee shop where I immediately feel unqualified to be at by virtue of its cool artsy factor. I bought this notebook envisioning it would be something I could pull out many times throughout the day, jotting down ideas I wanted to develop further, questions I was wrestling with, beautiful phrases I heard that I wanted to remember, even to-do notes or grocery lists. The kind of thing cool artsy people carry around. A sort of catch-all space to capture thoughts I don't want to forget. I also thought it could be a helpful tool to redirect the impulses that pull me into my phone and down The Infinite Whirlpool Called The Internet™️.

As is often the case with my creative aspirations, my notebook use has been far less consistent than I anticipated, as evidenced by the fact that this diminutive seventy-page pad still contains twenty-five blank pages one year into the experiment. I'm still trying to figure out how to make a habit out of spending more time with this little companion, and the draw toward The Digital Pocket Portal™️ is as tempting as ever.1 That said, I think some of my initial hunches were spot-on. While many of the ideas I've jotted down in my little notebook have simply stayed there and gone nowhere else, a decent amount of them have made their way into one of these essays, prompted a meaningful conversation with a friend, or simply caused me to notice something that ever-so-slightly shifted how I experienced the remainder of that day.

As the experiment slowly evolves, I'm grateful that this small paper friend—with its bent spiral binding, frayed edges, and twenty-five blank pages of possibility—keeps me company each day.

I'm not going to tell you how "using a notebook in these three ways will change your life!" There is a whole world of YouTube videos, podcasts, and blogs covering the art and technique of pocket notebooking (a world I'm slightly embarrassed to admit the depths of which I've explored!). I do think there's plenty of value for each of us in finding some way to take our thoughts out of our brains/bodies and place them intentionally into some container. The particular medium and the process will surely look different for you than it does for me, as will what you eventually decide to do with those thoughts—whether they translate into some publicly shared creation or simply enrich your personal life.

However, I do suspect there's one element of the note-taking process—or more broadly speaking, of the creative process—that we'd all be better off if we reckoned with from the outset: it's a messy process, and that's ok. I'd even argue that that’s a good thing!

Giving Up on the Perfect Process

I've tried various systems in the past for journaling. During grad school, I obsessed over building the perfect template in Notion for a weekly reflection and planning journal—and I definitely spent more time tweaking the template than actually reflecting or planning with it. I've used a journaling app on my phone and computer called Day One—both typing and audio recording entries. I've carried around large, leather-bound notebooks to try my hand at the pen-and-paper route. When I think of ideas that I might want to turn into essays someday, I've often dropped them into a "second brain" database in a notetaking app called Obsidian.2

And I do use several of these tools with regularity. The shift has been that lately, I've given up looking for "the perfect process," because I'm skeptical that "the perfect process" for journaling or writing or note-taking really exists. The process is all contextual: it depends on what my work looks like, what my calendar looks like, what I'm needing in a given season, how much energy I'm taking into a given day, even what tools are available to me in a given moment. And all of these factors are liable to shift over time; therefore, so is my process.

In a certain sense, the best process for journaling, writing, ideating, and creating is the one I'm committed to using in the present moment. Because that's the only one I actually have.3

There's still a sizeable part of me that longs for a perfect system. And to be sure, there are certain processes and tools that I do feel like I've well optimized for my current purposes. And that feels good to me, so I'm not advocating against this sort of thing.

But there's another part of me that recognizes that the processes that work well for me right now might not carry into the future. Presently, I have a half hour walk to my office each weekday, and so I know that the first ten minutes of that walk are a perfect time for some audio journaling time to sort through the yesterday’s events and the thoughts I'm waking up with. But who knows what lies ahead? If my future contains a car commute, a work-from-home schedule, or if work simply looks very different for me, maybe my audio practice will have to shift to accommodate that new context.

The Mess is a Signifier

One of those aforementioned pocket-notebook/journaling gurus, a guy named even Foster, made a point in this video that resonates. Like me, his first instinct was to look for the perfect system. And like me, he soon realized that if he's looking to create the perfect system on the fly, he is bound to record various imperfections along the path—especially if, like me, he's writing with a pen and not a pencil!

Foster explains that he began using his notebook to track when packages would arrive at his door, so that he would stop obsessively checking his Amazon and USPS notifications. This is, of course, an imprecise method, and so he quickly found that he would end up crossing out dates and rewriting them, and the page would turn into a bit of a mess. And it's at this point that Foster realized that "the mess is a signifier." Crossing out lines, trying new systems, iterating through the process over and over, the physical record itself of the process gets messy. And that messiness is counterintuitively a sign that something intentional and important is going on here.

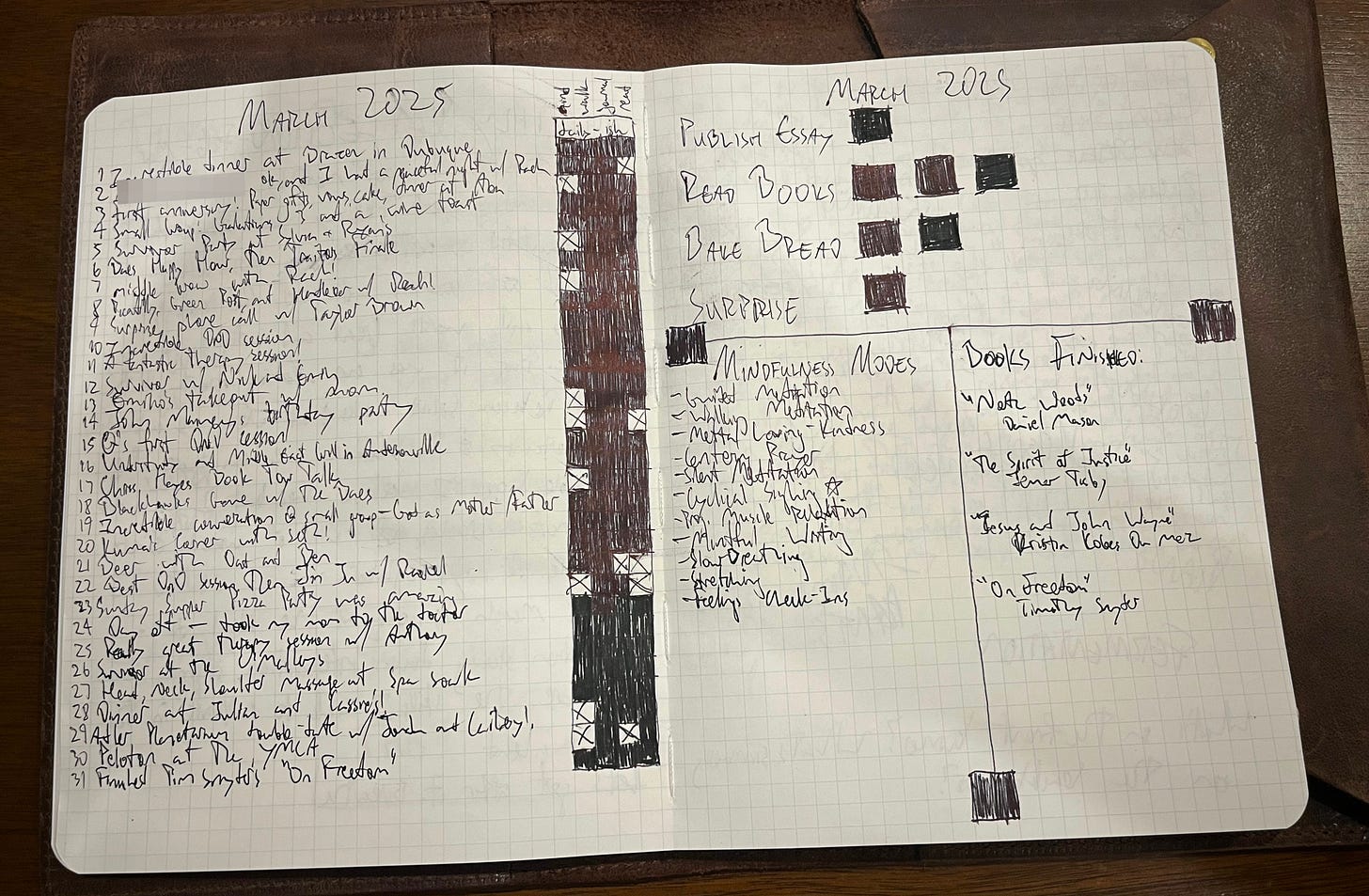

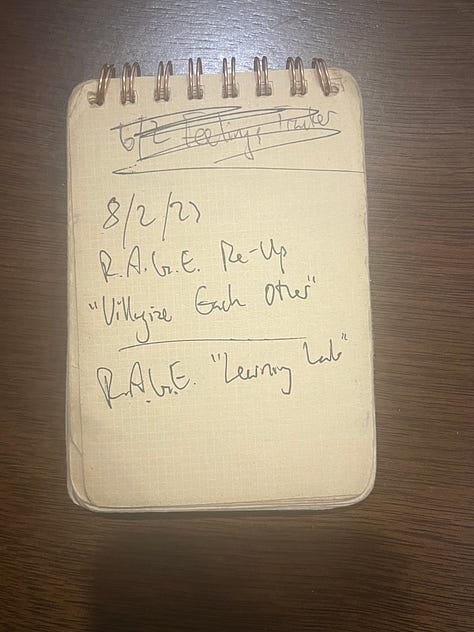

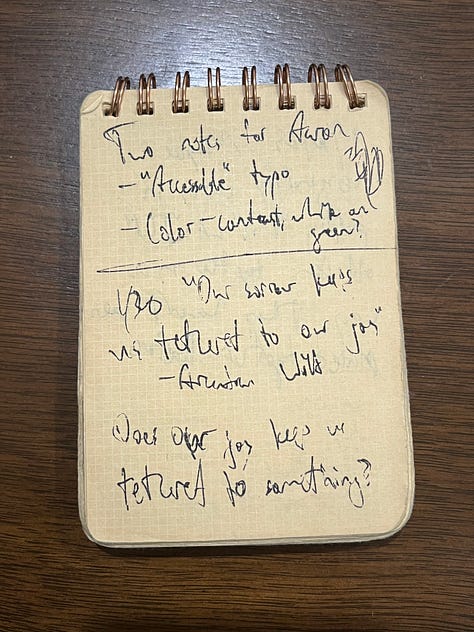

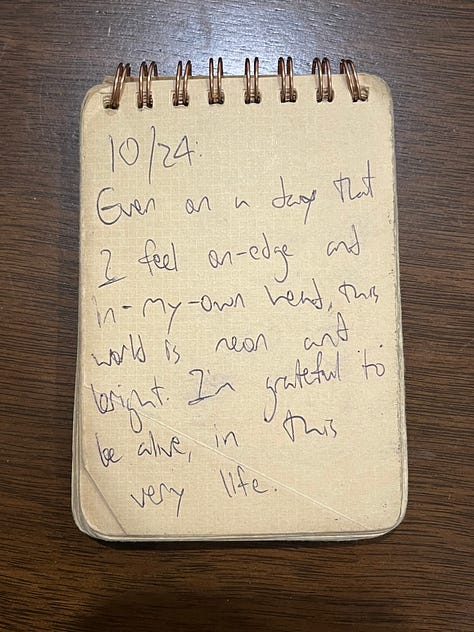

A parcel tracking notebook might be a mundane example, but I find the general principle very compelling. Just flipping through a few pages of my pocket notebook, I see to-do lists, quotes from books, notes from church, questions for myself, meeting reminders, and therapy takeaways. I see some pages with dates, some without them. Some words are crossed through. Some pages are torn out or creased in half. A few pages have one word, and many have long run-on sentences. It’s ever evolving, and it’s far from organized.4

In my monthly journal—the place where I track habits, note daily highlights, and set out monthly goals, I see small tweaks from month-to-month: new habits tracked, small 'artistic'5 embellishments on the borders, months where I clearly switched pens halfway through after losing the pen I started the page with.

The mess is a signifier. Because when I set out to create the perfect system for myself, I set a bar so impossibly high that it demotivates me from taking even one positive step forward. I realize quickly that I can't execute the perfect system for journaling or publishing these essays, and so I give up before I really even start.

But when I lean into the mess and looks for the clues therein, I can give up on "perfect" from the get-go and actually do something. I look back previous essays I’ve written and wish I would have included a clarifying point, edited a sentence out, or concluded with a different question. I cringe when I see I’ve repeated an overused cliche and frequently ask myself if my words make sense to anybody else.

But then I recognize that if I waited until I felt entirely confident with the quality and coherence of my words before hitting “Publish,” I would simply never hit “Publish.”

The word “essay” comes from the French essai, which simply means “to try.” Try. Write. Create. Share the mess proudly. It’s a sign.

Messiness as a Path to Emergence

Earlier, I said that the messiness of an imperfect process is not only not a problem, but actually a good thing. Here's why: it is this very messiness that allows for emergence to take place. Quoting Nick Obolensky, writer and activist adrienne maree brown explains that emergence "is the way complex systems and patterns arise out of a multiplicity of relatively simple interactions." She notes that nature is rife with examples of emergence: "Birds don't make a plan to migrate... They feel a call in their bodies that they must go, and they follow it, responding to each other, each bringing their adaptations." Tree roots, fungi, worms, and burrowing creatures all interact below the forest floor to each others’ mutual benefit, though no conductor is orchestrating this symbiotic song and dance. Each cell in each of our bodies is not consciously aware that it's a cell in a magnificently complex creature, and yet they organize and coalesce to form us humans, and us humans in turn form "systems, movements, societies."

It is this connection between simple individual interactions and remarkably complex patterns that define emergence. In Emergent Strategy, brown calls this a fractal connection. Fractals are patterns that repeat themselves over and over; they're "self-similar" on small and large scales. Think about an oak tree: it begins as a large trunk then splits into two or three main branches, then those branches split and they split again and again until they terminate as thin twigs. And at the end of each twig is an oak leaf that itself fans out into finer and finer veins. Emergent practices are like that. Each simple, individual step mirrors the larger patterns that are generated over a long time.

In brown's words: "Small is good, small is all," because "[t]he large is a reflection of the small."

So when I say that the messiness of an imperfect creative process is an emergent process, I mean that every stroke of a pen in my notebook—including the strokes that cross out what I perceive to be "mistakes" or "accidents"—builds toward beautiful future patterns. And I cannot possibly predict what those patterns will be. For that is another essential trait of emergent processes: they're inherently unpredictable. You can only ever see the next step immediately in front of you. You might have hunches as to where that step could lead you, but you can never say so with certainty. You simply "do the next thing." And iterating over the next thing and the next thing and the next thing6 can lead to some wonderfully unexpected places.

Think of it like a garden box being prepared in the spring. In this one, I mixed up some new compost with last year's potting soil, traced shallow lines across the surface from end-to-end, and sprinkled a bunch of radish seeds in the depressions. I could be fairly sure (thought not certain, strictly speaking) that the sprouting seedlings would be radishes. But I could not possibly predict how many would sprout, whether the radishes would grow plump and stout or long and skinny, or even how peppery they might taste. I had no clue when I sowed these seeds that we'd plunge straight into a dust storm then a week of cold rain. And that's to say nothing of how I'll prepare the harvest in my kitchen or whatever I'll plant in that box next.

That's what the pocket notebook is like for me. I might write 87 thoughts in a notepad and it's only the 88th that I latch onto and run with. But it might be that I never would have arrived at Thought #88 without first wading through the waters of Thoughts #1-87. Each scrawl, scratch, and sketch is a seed sown.

Finding the Mess

This perspective is not just for writing either. So many meaningful practices can take an emergent form, and looking for the proverbial scribbles can point us in the right direction.

Here's just one example: I have a dream of one day opening a cafe where neighbors can rub shoulders with each other in a welcoming space and eat a delicious meal for free. I can't finance or execute that right now, but I can invite folks into my own home for dinner parties. Every time I burn the bottom of a pizza and set off the smoke alarm, I learn that the cultivation of community is not dependent on me being a perfect host. Every time a friend-of-a-friend-of-a-friend shows up unannounced, I learn that there's room at the table for a stranger looking to connect.

The mess is the sign. And the signs are plentiful.

My college professor David Dark would often say that "to love a person is to love a process." If this is true (and I think it is), then learning to embrace our imperfect processes can be an act of compassion. To continue pulling out that beat-up little notebook from my front-left pocket—and to continue sharing my words in this space even when they feel imperfect and inadequate—is to honor a living journey whose end I cannot predict. On the flip side, to seek perfection from the outset nearly guarantees that I'll miss out on every wonderful surprise of that journey-that-could-have-been.

What's the mess that you can take the first step to make? Where is it pointing you?

Above all, trust in the slow work of God.

-Teilhard de Chardin

If you liked what you read here, give my previous essay a read. And if you’re up to read more of my words, you can find me on various other socials (for now) @lladnar42 and sign up for my email list by clicking the “Subscribe now” button below.

Lastly, if you’d like to contribute something to this conversation—a thought, a question, a piece of pushback—I’d welcome that. Go ahead and share something in the comments below!

I've found more success in this battle by letting go of the binary success/failure framework as I renegotiate my relationship with my digital devices, but that might be a story for another day.

See? I'm not anti-tech. Just anti-infinite-scroll.

If this idea about the inescapability of the present moment is your jam, I cannot recommend Oliver Burkeman’s newsletter The Imperfectionist enough. You might start with this one, where he writes: “We want to find some person, or some philosophy of life, that will spare us the fear or discomfort or self-doubt or tedium that so often seems to come along for the ride, whenever we try to make progress on things we care about. We hate feeling yoked to reality in such an unpleasant way; we long instead to soar above it, in a realm free from problems. And it’s the mark of a bad self-help book, a dodgy spiritual guru or an incompetent therapist that they’ll be only too happy to encourage the illusion that this might one day be possible.”

Stepping back to re-arrange the mess into something organized, cohesive, and narrative is its own joy. The transition from “puzzle pieces scattered across the table” to the picture snapping into place can be so gratifying. As (I think?) Brian Eno says, “Slow preparation, fast execution.”

You have my full permission to imagine comically exaggerated air quotes.