Connection is joy and connection is responsibility.

I wrote the above sentence in my previous essay. I wouldn't call it a throw-away line, though I will admit that I wrote it quickly and moved on.

But a few hours after publishing, my friend Sylvia shot me a text saying how much she appreciated that line specifically.

And her text got me thinking a little more about what exactly I meant by that dichotomy. Why does joy accompany the experience of connection? And what sort of responsibility does this experience of connection call us to?

I set my phone down and went on my way to tidy up around our place. As I did so, I was hit with a ping of gratitude for the color and comfort in our home. Rachel and I have spent a lot of time crafting our apartment into a place to feel happy and rejuvenated coming home to (and in her case, working from). And as I was hit with this ping of gratitude, I wondered what exactly about our home makes me feel so happy and comfortable. No doubt, the cozy lighting from lamps scattered about, the furniture that matches both our tastes, and the various creature comforts all contribute—each of these things a privilege in their own way.

But I quickly zeroed my answer in on a common denominator: those elements of our home that bring me the most joy are the elements that establish a sense of connection with people I love.

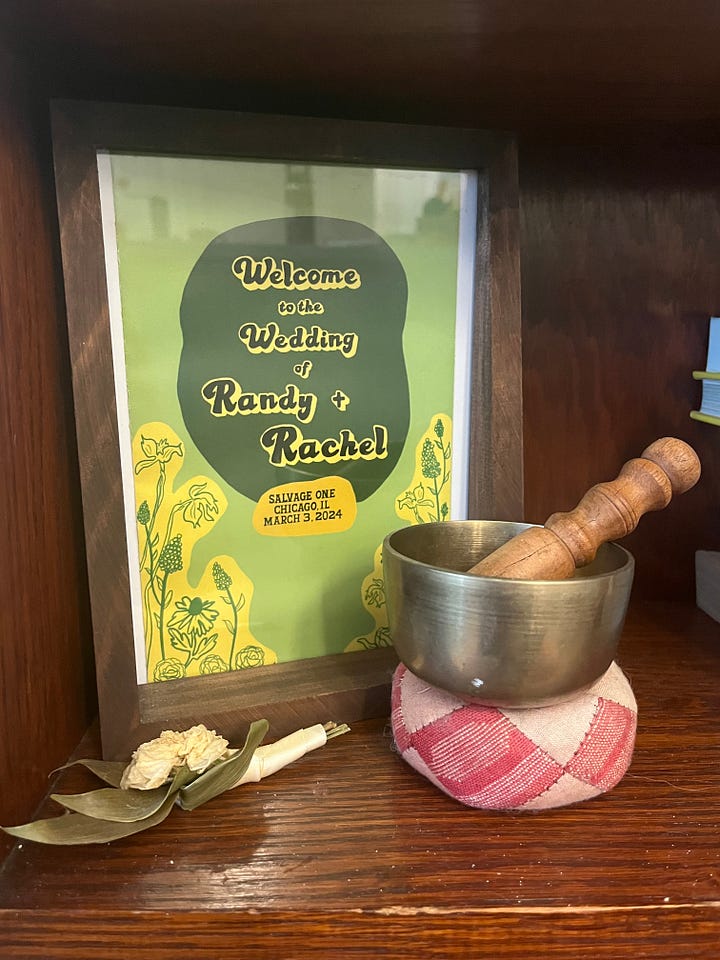

Like this framed program from our wedding and this portrait of my childhood kitty, both crafted by our fabulously talented friend Gabbie (follow her here!!):

Or this gorgeous print from Scott Erickson, one of three my Mom gave me to spruce up my drab seminary apartment bedroom:

Or these two chef's knives, which I pull out most often when I'm cooking, each given to me by one of my brothers:

And even these little seedlings—the canna lilies brought from my friend Chris's garden and the shishito pepper passed over my neighbor's fence into my own hands—bring me a great deal of joy:

Of course, the thread that ties each of these objects together is that they were gifts. Not something we obtained through a monetary exchange, nor something bestowed upon us freely by the mystical forces of the Chicago alleys (IYKYK). No, these objects were chosen with intention and care, given to us without any expectation that we would transact something of equal value in return. And the presence of these gifts enriches our home far more than the sum of their market values.

Each gift that speckles the landscape of our home is a touchpoint, a tangible reminder of the connection that's been established between folks who love one another.

And this reveals something of the joy of connection: moments of connection are moments of love. Even when such connection occurs in less-than-happy circumstances—at a loved one's funeral, as a community recovers from a harsh storm, as folks congregate to protest the grave injustices that have taken root in our land—those moments still evoke a sense of "aliveness." That's the term Christian Dillo and Oliver Burkeman use to best approximate that utterly human feeling that's hard to put words to: aliveness “isn’t about feeling better; it’s about feeling better.” It's the sense that we're really here, really tapped into our humanity, really... connected!

Connectedness and Gift Economies

The Potawatomi botanist Robin Wall Kimmerer has convinced me that a key to fostering these experiences of connection and aliveness is to build what she calls "gift economies." She lays it out brilliantly in her little book The Serviceberry (only 105 pages, with beautiful illustrations!). A scientist by trade with a deep knowledge of Indigenous ways of navigating the natural world, Kimmerer sees an abundance of clues in that very world for how we humans might construct alternate economies.

Whereas market economies are built on an explicit expectation of 'equal-value transactions'—and more specifically, whereas "cutthroat capitalism" sees the world as a pool of resources to be continually extracted—Kimmerer's gift economies understand wealth and value in a fundamentally different way. Such economies, she explains, include "a system of social and moral agreements for indirect reciprocity, rather than a direct exchange." And thus, "the currency in circulation is gratitude and connection rather than goods or money." When a participant in a gift economy finds themself with an abundance of something—for example, a bumper crop or more books than they could possibly read1—they naturally share it with their neighbors. And the back-and-forth flow of gifting and receiving over time ensures that there is enough for everybody. Nobody in the community is abandoned to suffer the violence of scarcity.

There's so much more I want to say about this incredible little book, but for the scope of this essay, let it suffice to say that gift economies build relationships of reciprocal care, and that is unequivocally a good thing.

I see it when I think back to the pothos propagation we handed over the fence to our neighbors last summer in a mason jar, and the way it came back to us this summer in the form of that shishito seedling. Their backyard garden is magnitudes more robust than ours, and I'm excited for us each to share our harvests throughout the season.

I see it when I walk around the neighborhood and spot various outposts of the gift economies staked in the ground. They're almost always called "little libraries." There’s lots of the kind that most of us are familiar with—the little boxes with a glass door containing a mishmash of used books.

But I see novel applications as well. There's the little seed library where I took two extra bean seedlings in hopes that another gardener would pick them up and plant it in their ground.

And the little art library, filled with trinkets, bud vases, small prints, even postcard poems, all for the taking with a kind admonition to not be greedy (for greed always jams the spokes of the gift economy).

But my personal favorite is the dog stick library one street over from our place. Notice how thoughtfully its designers placed the largest sticks on the top shelf for the big dogs and the smallest twigs on the bottom shelf for the little pups.

I've noticed more and more of these gift micro-economies lately. It's hard to say if that's because their numbers are growing or because my eyes are simply opening up. Either way, I'm glad for their presence and the connectedness they cultivate in our neighborhood.

Gift economies operate on scales small and large. I see it too in the way my church, Grace Church of Logan Square, is committed to using its building as a gift for the neighborhood. After church leadership considered selling the century-old building in the wake of the pandemic, an outcry from neighbors not to surrender another anchor-point to land-hungry developers shifted the congregation’s perspective: what if, instead of this building being a financial liability, there stood before them a responsibility to understand it as a gift to steward for the community's sake? AA groups, basketball leagues, resident artists, and grassroots mutual aid organizations like The Trash People have found homes in every corner of Grace's edifice, for free or rent far below market-rate.

Kimmerer ponders how and whether these gift economies can be scaled up. Market economies are well-entrenched in our modern world, and to some degree we have to "play the game" to survive in America. But until some seismic shift alters that basic fact of life, she suggests that we can still participate in gift economies in parallel with the market, as an alternative that seeks a more hospitable way of living with our neighbor. It can take so many forms: sidewalk clothing swaps, "Buy Nothing" Facebook groups, even open-source coding shared online across vast distances.

And each gift economy captures succinctly what I mean when I say that "connection is responsibility." Our collective fate is in one another's hands. Our communities are stronger, more resilient, more imaginative, and more abundant when we take one another's flourishing seriously and step outside of the "survival of the fittest" paradigm. Gift economies teach us to stop seeing one another as strangers in a zero-sum game and start seeing one another as neighbors in a world of latent abundance. I've heard it described as "village-mindedness."

My encouragement to you is to consider where you've seen gift economies in your own life. They don't have to be large or fancy or formal and they might pop up in surprising places. And you ponder, I'll leave you with one more guiding principle from Robin Wall Kimmerer (and seriously, just close this tab and get her book):

"To name the world as gift is to feel your membership in the web of reciprocity. It makes you happy—and it makes you accountable."

If you liked what you read here, give my previous essay a read. And if you’re up to read more of my words, you can find me on various other socials (for now) @lladnar42 and sign up for my email list by clicking the “Subscribe now” button below.

Lastly, if you’d like to contribute something to this conversation—a thought, a question, a piece of pushback—I’d welcome that. Go ahead and share something in the comments below!

This may or may not be a note to self…

Such a beautiful piece, Ran ❤️.

Hi Randall, I love being part of the gift economy! I write SolarPunk short stories that explore hopeful visions of a greener, healthier future. I also share blog-style reflections on my journey towards living more sustainably here in suburban Australia. I’m passionate about the non-monetary economy, so if you’d like a complimentary virtual one-on-one sustainable living consultation, just send me an email (sustainable.saffy@gmail.com).