I was just trying to figure out what to do with that extra crown of broccoli sitting in my fridge.

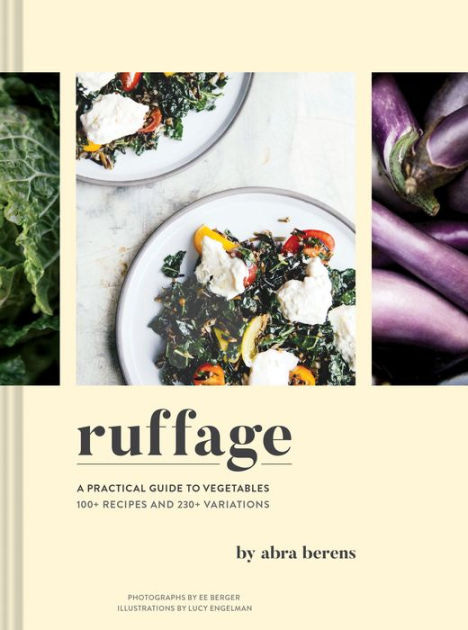

The other night, I was planning ahead for the next day's supper. So I reached for my latest used bookstore find: chef/farmer Abra Berens' brilliant Ruffage: A Practical Guide to Vegetables. I had been eyeing the title for well over a year, and I couldn't say no to the modest $15 asking price for this copy nestled on the lowest shelf of the store's cookbook section. I didn't notice until I got home that it had two post-it notes sticking out the top one really good smudge on the bottom-right corner, a great sign that this book was not just an uncontaminated trophy in its previous owner's home: it had been used, loved, handled, and passed on for reasons unknown.

I was thrilled. Ruffage is organized in a uniquely useful way. Unlike a traditional cookbook, which might be arranged according to the courses of a meal—appetizers, soups, salads, entrees, and desserts, for instance—Berens' recipes are organized by the vegetable that each dish features. There's a section for radishes, another for peppers, one for greens (leafy and hardy), asparagus, squash (summer and winter), and on and on. A veritable veggie bible, and a perfect resource for whatever plants happen to be lying around in the refrigerator.

And so, having taken inventory of my fridge's contents and taken note of the big broccoli crown resting on the middle shelf, I reached for Ruffage and flipped to page 91 to survey the corresponding recipes.

I appreciate the short introductions to each vegetable that Berens includes in the book. She draws deeply from her experience as a chef, a farmer, and a Midwesterner/Michigander. So before jumping straight to her suggested broccoli preparations, I began to read her short vignette of the best-known brassica.

But I must admit, I was just trying to figure out how I wanted to cook it. I didn't expect to be left breathless.

In the two-page essay, Berens recalls one morning four months after her mother died when she was staying at her parents' home and was awoken by the clanking of cast iron. She got out of bed and walked to the kitchen to find her dad cutting through a mountain of onions, a pound of bacon, and a forest of broccoli. The scene understandably surprised Berens, considering that her mother had done 95% of the cooking in her parents' home for her entire life. But quickly, she understood that her father "was trying to heal," and so she grabbed a knife, set down a cutting board, and jumped in to help.

The image of father and daughter preparing a meal in the wake of their mother/wife's death was arresting. Maybe because, in a not-insignificant way, it was familiar.

Food as a conduit

I'd venture a guess that it's a familiar image to anybody for whom food plays a significant role in their family culture and story. Such is the case with my kin. We do not gather around empty tables, and I don't know if we ever have. It matters not whether we're congregating on Christmas day or an ordinary Tuesday afternoon in June: you can expect us to be conversing over something nourishing.

We cook to eat and we eat to celebrate and we don't need grand excuses to celebrate. The other day, it was to commemorate the arrival my Mom's new couch to her living room, and French onion soup was on the menu. The time before that, it was the food itself we were celebrating: the calendar's turn to May marked the beginning and end of ramp season, and such fleeting joys are worthy of observation.

I've been lucky enough to stumble into a broader community of friends who understand the value of a festive feast, the power of a full table to cultivate a sense of belonging. DIY pizza parties, dining room cafes, a tray of homemade cookies showing up at work the day of a big project. I've found myself in the company of folks who understand that good food can be an effective conduit for community, for celebration, for that elusive feeling of aliveness.

But not every gathering is so obviously joyful and not every meal so obviously a celebration, at least at first glance. For aliveness, community, and even celebration can be found in moments of sorrow and grief too. And in these sacred spaces, food can nourish the soul yet.

We gathered at Mom's house in the afternoon on Thanksgiving of 2023. She, my brothers, our partners, and I all brought the requisite components for our traditional feast. But this Thanksgiving was different, because Mom had called that morning to let me know that my Grandma M had passed away peacefully in the presence of her two children.

It felt strange to celebrate the holiday, and yet it would have felt far stranger not to gather, not to cook, not to eat—not least because because Grandma M, the matriarch of our little family, was as responsible as anybody for the institution of a shared meal at every gathering. And so, we gathered in the kitchen to prepare a meal together: glazing the Brussels sprouts in sticky maple syrup, stirring the gravy to top the fluffiest potatoes, dressing the salad. It was a rather simple Thanksgiving meal, and the spread was far too large for our appetites that day. The table was bountiful, broad enough for every stroke of sorrow, joy, aching, laughter, longing, and gratitude that settled on our hearts that day.

As my brothers and I put the finishing touches on the spread, I looked over to the couch and saw my niece sitting on Mom's lap. They cracked open a book—Henry and Mudge. Mom read to her granddaughter with a soft, tender voice. Both seemed entranced, at ease.

"Dinner's ready," I croaked through a soft smile.

The way we started trying

I don't care to explicate that scene any more than to say that cooking a meal and sharing it with people I loved was what I needed right then, and it seemed to me that they needed it too.

Each chop, each toss, each stir, a signal to my body that it is in the right place. Each sip and bite a memo to my soul that it is in good hands.

More often than not, my first step after something terrible and after something terrific is to see what's in the pantry and who will share it with me.

Berens captures the essence of the experience brilliantly (emphasis mine):

The grief isn't gone. It never will be. Somehow it still feels disloyal—to have continued to live and not be so sad every day. We had to try. We had to start doing the things that you do in normal life—normal life before you realize that it is possible to die. Before you learn the lesson that absolutely everything is fragile and can break irreparably in a moment when you're not looking.

The way we started trying to heal was through food.

It's the way I know how to start trying, too.

And so the other night, I set Ruffage aside and grabbed for a cookie I had made earlier that evening. It was one of Grandma M's old recipes, a rosemary sugar cookie. Except I had far more tarragon in the garden than rosemary, so I made the swap and they were divine.

I sent a picture to Mom, and she recalled that Grandma M would always send her a picture of her cookies fresh out of the oven.

I don't believe that celebration and grief are antonyms, nor do I believe that joy and happiness are synonyms.

I do believe that a meal with those I love is able to contain it all. The celebration of lives well-lived, the grief of wishing we could share this present plate with those lives. The joy of a sweet-salty-crunchy-crispy-pillowy-perfect bite hitting every corner of every taste bud, and the joy of each near-and-distant memory the bite evokes.

Berens is right. Grief does not exactly go away. We learn to live through the many griefs that pepper a human life. With grace, luck, love, and a lot of hard work, we heal through those griefs. I cannot say what that looks like for you.

But for me, tonight, it looks and smells and tastes like a tarragon cookie.

If you liked what you read here, give my previous essay a read. And if you’re up to read more of my words, you can find me on various other socials (for now) @lladnar42 and sign up for my email list by clicking the “Subscribe now” button below.

Lastly, if you’d like to contribute something to this conversation—a thought, a question, a piece of pushback—I’d welcome that. Go ahead and share something in the comments below!